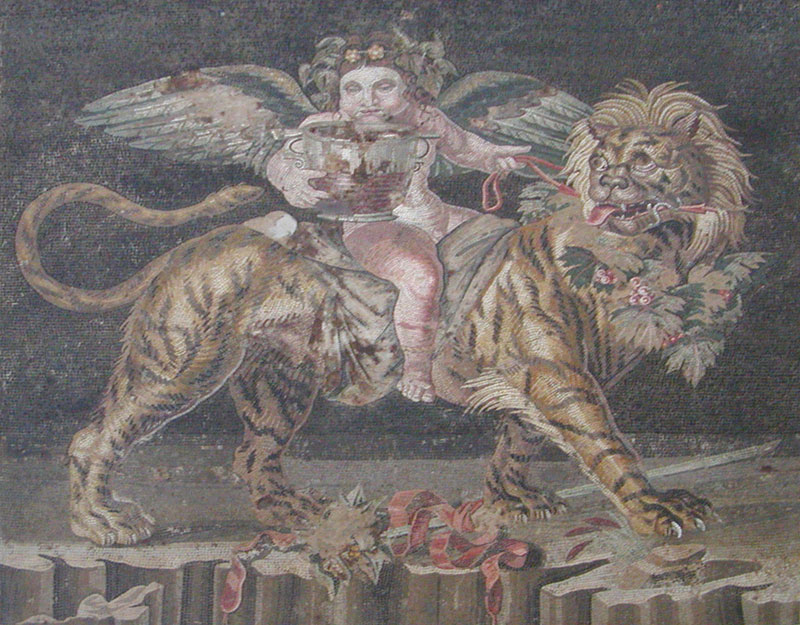

The Romans were partial to mosaic floors and many have been found all over the

empire. The Genius of Bacchus on a Panther below is from Pompeii.

The Romans were partial to mosaic floors and many have been found all over the

empire. The Genius of Bacchus on a Panther below is from Pompeii.

The Romans were partial to mosaic floors and many have been found all over the

empire. The Genius of Bacchus on a Panther below is from Pompeii.

The Romans were partial to mosaic floors and many have been found all over the

empire. The Genius of Bacchus on a Panther below is from Pompeii.

Porsena, admirans virtutem Muci et timens alios Romanos qui eum interficere volebant, Mucium

Porsena, admiring the bravery of Mucius and fearing other Romans who him to kill they wished, Mucius

.

Romam dimisit. Deinde ex agris Romanis copias reduxit

to Rome he let go Then out of the fields of Rome troops he lead back

.

et Rome salva erat. Postea Mucius "Scaevola" appellatus est quod dextram manum amiserat.

and Rome saved it was. Afterwards Mucius "Scaevola" he was called because his right hand he was missing.

.

Scaevola means "left hand" or "left handed"

It is pronounced "Skywola"

Porsena, admirans virtutem Muci et timens alios Romanos qui eum interficere volebant, Mucium

Porsena, admiring the bravery of Mucius and fearing other Romans who him to kill they wished, Mucius

.

Romam dimisit. Deinde ex agris Romanis copias reduxit

to Rome he let go Then out of the fields of Rome troops he lead back

.

et Rome salva erat. Postea Mucius "Scaevola" appellatus est quod dextram manum amiserat.

and Rome saved it was. Afterwards Mucius "Scaevola" he was called because his right hand he was missing.

.

Scaevola means "left hand" or "left handed"

It is pronounced "Skywola"

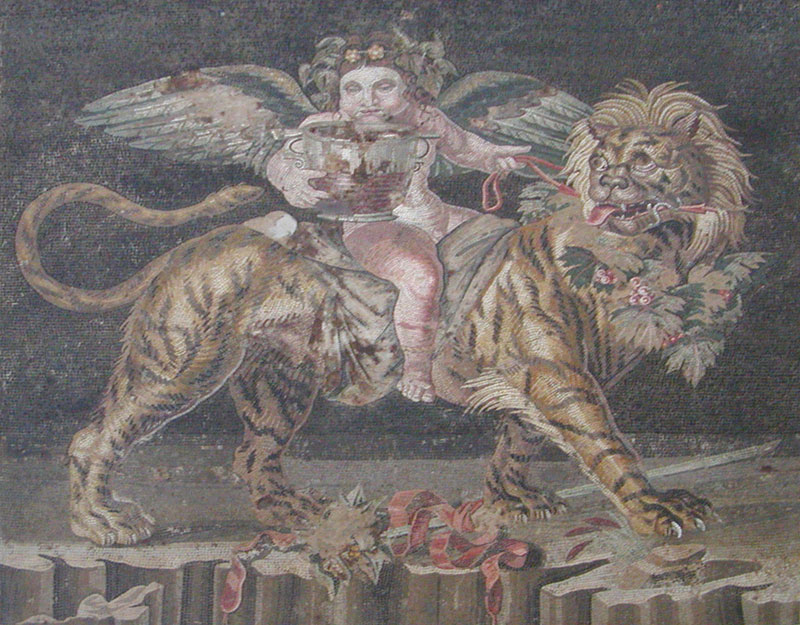

It is said that the Romans learned the practice of using gladiators from the Etruscans. The Etruscans, when they captured enemy soldiers, would force them to fight each other. The Romans first did the same with enemy soldiers, but later used slaves and convicts. It was said that professional gladiators would greet the presiding official with the words "Morituri te salutant!" - Those about to die salute you!

So great was the Roman's love of the sports of the arena that every city of note had at least one amphitheater. While the Coliseum at Rome is the largest and best known, there are substantial remains of others in numerous cities today, notably at Pompeii, Verona, Nimes, Aries, and Pola. The games which took place in the amphitheater were chiefly gladiatorial and vied in popularity with the races in the circus.

At first the gladiators were captives taken in war, but later slaves and convicts were trained to this profession in regular gladiatorial schools. These schools were controlled by companies somewhat after the manner of those which handled the chariot races in the circus. As in the case of the races, the games were usually given by officials or wealthy men seeking popularity, and, during the Empire, by the Emperor. The giver of the games made arrangements with the manager of one of the gladiatorial schools and the games were run off as stipulated. Sometimes five hundred pairs of gladiators fought in the arena at the same time.

Of special interest were the combats illustrating the equipment and methods of fighting used by different tribes and peoples whom the Romans had conquered. Wild beasts were another popular feature of the arena. Some- times they were pitted against each other, sometimes against gladiators. To protect the spectators from the possible attack of wild beasts, the arena in the Coliseum was surrounded by a wall some fifteen feet high and surmounted by a grating or bars for additional protection.

For successful gladiators there was prize money, which sometimes reached astounding proportions, though never so great as for the successful drivers in the chariot races. But the great gladiator enjoyed a personal popularity exceeding even that of the successful charioteer.

The Romans were especially fond of naval battles, which were a feature of the games in the Coliseum, although less frequent than the regular gladiatorial combats. Under the arena at the Coliseum there were rooms for gladiators and for beasts. Here, too, were pipes by which it might be flooded for naval spectacles and then drained.

Despite the fame of the successful gladiators, and due to the nature of the games, a great deal of the participants were unwillingly thrust into the games.........which lead to rebellions. The first large rebellion occurred in Sicily in 135 BC. Although more than 70,000 slaves revolted, the Roman army crushed the rebellion two years later. A second rebellion occurred in Sicily 104 BC. and lasted four years, until the remaining slaves were captured by Manius Aquillius and sent to Rome to fight in the arena.

Gladiators took their name from the Latin word "Gladius" - sword. Gladiators normally carried a helmet, a sword, a shield and an armored sleeve on their right arm. One variation of this was that of the "retiarius" who fought with a trident, (a spear with three points at the end) a dagger, and a fishing net used to snare the opponent.

When a gladiator was wounded, the victor would look to the crowd for a signal as to whether his life should be spared or not......and the crowd would decide, based upon his bravery if he would be allowed to live. If the crowd was divided in its opinion, the sponsor of the games would make the decision. There seems to be some debate between historians as to whether a thumbs down meant - let him die! or, let him live.........

The Romans developed Gladiatorial schools to train their slaves and convicts in the art of fighting before they were considered ready to fight. There were several slave rebellions, due to the maltreatment of slaves and their unwillingness to participate in this bloody event.

It was at the School of Lentulus Batiatus that the largest of all rebellions broke out, one that was considered a threat to Rome itself.

The gladiators seized knives and anything else they could find and use as a weapon from a kitchen, and overpowered the guards, climbed the enclosing walls and escaped. They were then able to capture a wagon loaded with gladiatorial weapons........as they crossed the country-side, they raided estates of the wealthy landowners, and acquired more weapons and......more manpower as slaves deserted their masters to join what was becoming a dangerous fighting force.

Clodius Glaber assembled a fighting force of about 3,000 Roman soldiers to give pursuit, and caught up with the rebel force which had just climbed the dormant volcanic mount Vesuvius. Clodius fortified his position at the base of the mountain at the only road leading to the top, with the intention of starving the rebels into submission. Knowing that staying put would be suicide, the rebels hacked vines from the side of the mountain and used them to descend from it at night, and attacked the Roman camp, defeating the Roman camp, acquiring more weapons and armor.

Publius Varinus was soon sent from Rome with two legions (a legion is 4,200 to 6,000 men divided into ten cohorts) to catch the rebels and punish them. Publius, however, was unaware that the gladiator's army had increased in size to nearly 40,000 men. 2,000 of Publius' men were annihilated near Vesuvius when the gladiator army caught them by surprise. Another Roman contingent under Publius' lieutenant Cossinius was nearly encircled near Herculaneum, pursued, trapped and destroyed. Shortly afterward, as Publius continued the chase, the rebels turned upon him, nearly capturing him.......capturing his horse, insignia and official standards.........an act that humiliated the Romans.

Soon though, a rift developed in the leadership of this ragtag band of soldier-slaves. While Sparticus advocated marching to the north, and crossing the Alps to get away from the Romans, Crixus advocated assailing Rome itself. Since I am not playing the historian here, I will venture to say that I believe Crixus was correct in his assessment of the situation......the Romans were unprepared for anything of that nature, while the running advocated by Sparticus gave them time to gather forces.

That said, the result of the rift was the division of the forces; some went with Crixus, some with Sparticus. At about this time, (in the spring of 72 BC.) The Roman Senate put four legions on the field to intercept the rebel army. Crixus was surrounded and lost about two-thirds of his army to the fighting that ensued. What remained of Crixus and his band was soon destroyed.

After this, as the Romans pursued Sparticus, he soundly defeated them in three engagements, then a local governor Caius Casius in Mutina (Cisalpine Gaul in northern Italy) raised an army of about 10,000 men to stop the rebels, but was defeated and the captives were forced to fight each other as gladiators to avenge the death of Crixus and his men.

What really alarmed the Romans at this time was that after this battle, Sparticus turned south, in the direction of Rome.......and Rome had no battle-hardened troops to defend itself with.........they were all away, in Spain or Asia Minor. Marcus Crassus, who had served under Sulla, offered to take supreme command of the forces that were left after previous battles and a few hastily put together legions. Crassus then sent Mummius to bring the two new legions up to the rear of the rebel army but ordered them not to engage in battle with it; Mummius made the mistake of engaging the enemy, attacking and was defeated soundly, with the newly recruited soldiers, who, seeing battle for the first time, ran away.

Crassus was infuriated and ordered that the 500 or so men who were accused of cowardice be divided into groups of 10, lots drawn, and the loser being executed as a warning to the others not to repeat such behavior in the future.

Crassus then prevailed in a battle in the south, and Sparticus headed toward the costal city of Rhegium, with plans of bargaining with the Sicilian pirates and offering them the loot they had gathered from plundering to transport his troops to Sicily, where he thought he might be in a stronger position and gather more rebel slaves from the Island. The Sicilian pirates, however, deceived him and took the loot but never show up to transport his troops!

When Crassus realized that he had the rebel army hemmed in, rather than attack them, he built a huge wall 32 miles long across the peninsula, complete with a ditch 15 feet deep. With winter setting in, and running short on supplies, Sparticus waited for a winter storm and filled in a part of the ditch and escaped from the trap.

Unfortunately, once again the rebel army was divided due to differences of opinion on what strategy they should adopt. Two Gauls, Cestus and Ganicus broke off from the main group to plunder, were taken off guard by Crassus' army and nearly annihilated. Rescued by Sparticus, the whole rebel army retreated to the mountains of Petelia. Harassed by two Roman legions of Crassus' army as they retreated, they suddenly turned upon them and defeated the two Roman legions in a fierce battle.

As word reached Sparticus that Pompey and Lucullus, two seasoned generals, were en route to put an end to the insurrection, it was determined that their best hope was to reach Brundisium and escape by sea. However, Lucullus reached Brundisium before the rebel army, effectively trapping them between two large armies. When Sparticus heard this, he deployed his forces before Crassus' army, the weaker of the two forces, and ordered that his horse be brought to him. To emphasize that any further retreat on their part would be out of the question, that there would only death or victory in the coming battle, he slew his horse.

As the battle ensued, Sparticus spotted Crassus in the opposing army and made an enormous effort to reach him. Slaying two centurions in his path, he nearly made it, and fought with valor even after being badly wounded, until he and his bodyguards were surrounded and killed.

As some of the remnants of Sparticus' forces were captured, (about 6,000 men) they were crucified on the whole road from Capua to Rome. In this way ended the largest and the last great slave rebellion.

Despite the rebellion, the popularity of the games only increased, and at their peak around the 4th century AD. 175 days a year were devoted to them. The games eventually lost their popularity and were ended by the Emperor Honorius in 404 AD.

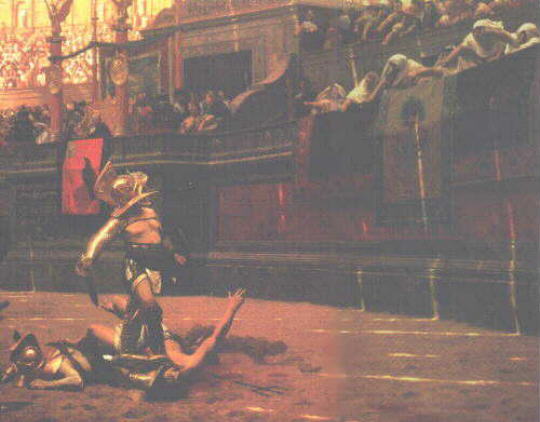

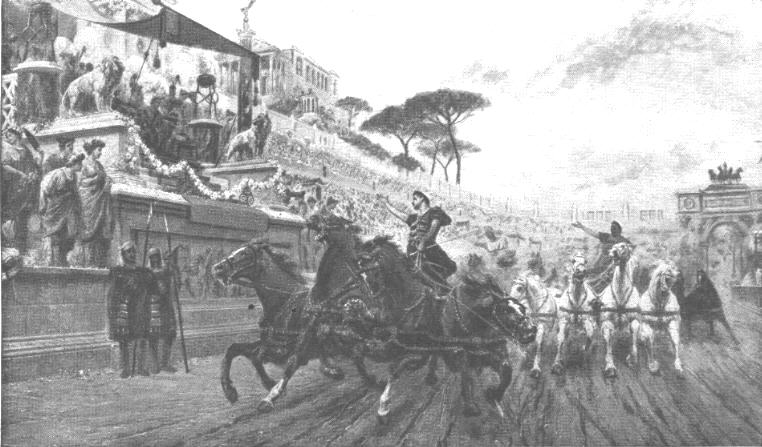

Chariot racing was the most popular sport in Rome. It took place in the circus, a long, flat space curved at one end, and divided lengthwise in the middle by a wall called the spina. This was adorned with elaborate statues, columns, and obelisks. There were seats along both sides of the circus and around the curved end, while at the other end were towers and booths for the competing chariots. Each chariot had a separate booth. Once around the spina was called a curriculum (lap), and most of the races consisted of seven laps. The race finished at the barrier end where the chariots had started, and after the race, the victor drove around the circus and left by the Triumphal Gate at the curved end.

There were no rules for chariot races. The sharp turns at the ends of the spina made speed difficult and hazardous, and the Romans were more interested in the danger of the race, and the accidents to horses, chariots, and charioteers, than in the speed with which they drove.

The teams consisted usually of four horses, but there were also races for teams of two, three, six, and even more. Chariot racing came to be a regular business run by companies which maintained vast racing stables and hired out their teams to the Emperor or to any wealthy man who wished to give the games.

Betting was common and the populace idolized successful drivers, whose rewards sometimes reached fabulous sums. There is record of one driver who won over fourteen hundred victories and amassed a fortune of nearly two million dollars.

The greatest race course was the Circus Maximus, which was rebuilt several times until it finally seated about 200,000 people. The seats were banked as in a theater and there was a colonnade for protection in case of rain, as well as balconies for prominent officials, and later, an imperial box for the Emperor, who entered it direct from his abode on the Palatine Hill.